FAIR and Reproducible Research

Check out the following article in the Journal Scientific Data:

Wilkinson, M., Dumontier, M., Aalbersberg, I. et al. The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Sci Data 3, 160018 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2016.18

Use basic Git and GitHub

Version control is better than mailing files back and forth, even if its only for yourself:

Nothing that is committed to version control is ever lost, unless you work really, really hard at it. Since all old versions of files are saved, it’s always possible to go back in time to see exactly who wrote what on a particular day, or what version of a program was used to generate a particular set of results.

As we have this record of who made what changes when, we know who to ask if we have questions later on, and, if needed, revert to a previous version, much like the “undo” feature in an editor.

When several people collaborate in the same project, it’s possible to accidentally overlook or overwrite someone’s changes. The version control system automatically notifies users whenever there’s a conflict between one person’s work and another’s.

Teams are not the only ones to benefit from version control: lone researchers can benefit immensely. Keeping a record of what was changed, when, and why is extremely useful for all researchers if they ever need to come back to the project later on (e.g., a year later, when memory has faded).

Version control is the lab notebook of the digital world: it’s what professionals use to keep track of what they’ve done and to collaborate with other people. Every large software development project relies on it, and most programmers use it for their small jobs as well. And it isn’t just for software: books, papers, small data sets, and anything that changes over time or needs to be shared can and should be stored in a version control system.

Git is a version control system.

GitHub is one of several online platform for public and distributed Git repository access and sharing. Others are Bitbucket or Gitlab and large organizations often have their own instances as well (e.g. Uni Tartu has an own Gitlab).

Installation for Git for Windows with Git Bash, for Linux and MacOS users Git is available either through your package manager or base system.

Typically, you either start a) completely fresh from the start, b) with a local folder that you want to put under version control and share, or c) with an existing online GitHub repository, that you want to update or contribute to.

Create an SSH key file for Git commandline access to online repositories

Why Use an SSH Key?

When working with a GitHub repository, you’ll often need to identify yourself to GitHub using your username and password. An SSH key is an alternate way to identify yourself that doesn’t require you to enter you username and password every time.

SSH keys come in pairs, a public key that gets shared with services like GitHub, and a private key that is stored only on your computer. If the keys match, you’re granted access.

The cryptography behind SSH keys ensures that no one can reverse engineer your private key from the public one.

Key Points

SSH is a secure alternative to username/password authorization

SSH keys are generated in public / private pairs. Your public key can be shared with others. The private keys stays on your machine only.

You can authorize with GitHub through SSH by sharing your public key with GitHub.

Attention

Generating an SSH key pair

The first step in using SSH authorization with GitHub is to generate your own key pair.

You might already have an SSH key pair on your machine. You can check to see if one exists by moving to your .ssh directory and listing the contents.

Open the Git Bash (if you are on a Windows computer)

Git Bash

Then check if you already have a SSH folder:

$ cd ~/.ssh

$ ls

If you see id_ed25519.pub, you already have a key pair and don’t need to create a new one.

If you don’t see id_ed25519.pub, use the following command to generate a new key pair. Make sure to replace your@email.com with your own email address.

Attention

Note: GitHub improved security by dropping older, insecure key types on March 15, 2022.

As of that date, DSA keys (ssh-dss) are no longer supported. You cannot add new DSA keys to your personal account on GitHub.com.

RSA keys (ssh-rsa) with a valid_after before November 2, 2021 may continue to use any signature algorithm. RSA keys generated after that date must use a SHA-2 signature algorithm. Some older clients may need to be upgraded in order to use SHA-2 signatures.

$ ssh-keygen -t ed25519 -C "your@email.com"

When asked where to save the new key, hit enter to accept the default location.

Generating public/private rsa key pair. Enter file in which to save the key (/home/YOU/.ssh/ed25519):

You will then be asked to provide an optional passphrase. This can be used to make your key even more secure, especially if you are on a computer you don’t have the control over (like the university computer). If you are on your private computer you can skip it by hitting enter twice.

Enter passphrase (empty for no passphrase):

Enter same passphrase again:

When the key generation is complete, you should see the following confirmation:

Your identification has been saved in /Users/username/.ssh/id_ed25519.

Your public key has been saved in /Users/username/.ssh/id_ed25519.pub.

The key fingerprint is:

01:0f:f4:3b:ca:85:d6:17:a1:7d:f0:68:9d:f0:a2:db your@email.com

The key's randomart image is:

+--[ RSA 2048]----+

| |

| |

| . E + |

| . o = . |

| . S = o |

| o.O . o |

| o .+ . |

| . o+.. |

| .+=o |

+-----------------+

The random art image is an alternate way to match keys but we won’t be needing this. Add your public key to GitHub

We now need to tell GitHub about your public key. Display the contents of your new public key file with cat:

$ cat ~/.ssh/id_ed25519.pub

The output should look something like this:

ssh-rsa AAAAB3NzaC1yc2EAAAABIwAAAQEA879BJGYlPTLIuc9/R5MYiN4yc/YiCLcdBpSdzgK9Dt0Bkfe3rSz5cPm4wmehdE7GkVFXrBJ2YHqPLuM1yx1AUxIebpwlIl9f/aUHOts9eVnVh4NztPy0iSU/Sv0b2ODQQvcy2vYcujlorscl8JjAgfWsO3W4iGEe6QwBpVomcME8IU35v5VbylM9ORQa6wvZMVrPECBvwItTY8cPWH3MGZiK/74eHbSLKA4PY3gM4GHI450Nie16yggEg2aTQfWA1rry9JYWEoHS9pJ1dnLqZU3k/8OWgqJrilwSoC5rGjgp93iu0H8T6+mEHGRQe84Nk1y5lESSWIbn6P636Bl3uQ== your@email.com

Copy the contents of the output to your clipboard.

Login to your GitHub account and bring up your account settings by clicking the tools icon.

GitHub Account Settings

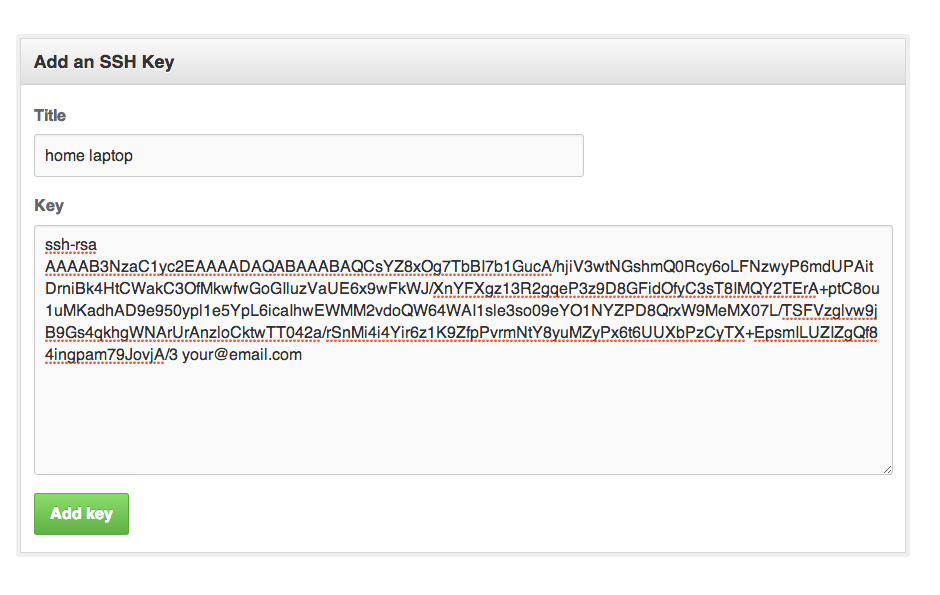

Select SSH Keys from the side menu, then click the Add SSH key button.

GitHub SSH Keys panel

Name your key something whatever you like, and paste the contents of your clipboard into the Key text box.

GitHub Add SSH Key

Finally, hit Add key to save. Enter your github password if prompted.

####Using Your SSH Key

Going forward, you can use the SSH clone URL when copying a repo to your local machine.

GitHub clone url options

This will allow you to bypass entering your username and password for future GitHub commands.

References:

a) Fresh start

Go on Github (or your preferred Git platform), and create a new repository. On Github or Gitlab it will tell you the exact steps to initial a fresh repository or link a local folder.

Something along those lines:

The repository for this project is empty

You can get started by cloning the repository or start adding files to it with one of the following options.

Command line instructions

You can also upload existing files from your computer using the instructions below. Git global setup

git config --global user.name "Alexander Kmoch"

git config --global user.email "alexander.kmoch@ut.ee"

Clone the new empty repository

git clone git@github.com:allixender/test.git

cd test12

git switch -c main

touch README.md

git add README.md

git commit -m "add README"

git push -u origin main

Push an existing folder into version control

cd existing_folder

git init --initial-branch=main

git remote add origin git@github.com:allixender/test.git

git add .

git commit -m "Initial commit"

git push -u origin main

OR Push and link an existing Git repository

cd existing_repo

git remote rename origin old-origin

git remote add origin git@github.com:allixender/test.git

git push -u origin --all

git push -u origin --tags

b) Local folder version control

Typically, you can start immediately and initialize Git version control with no further hassle:

git init .

And from hence you will do the basic workflow as follows, over and over:

git status

You can use/create the .gitignore file to ignore temporary or non-relevant files or prevent accidentally adding sensitive files to the version control.

The most basic workflow is checking with “git status” as seen above and selectively adding updated or new files to the commit process (staging) …

git add <file>

# or

git add .

The you commit (like checking in for good, register for history). Provide a message, for yourself or others, this will be related to that particular commit.

git commit -m "commit message for yourself or others"

If your local repository folder is already linked to an online Git repository, like GitHub, you can “push” the latest commits (aka) changes to the online version, where they are “safe” and can be seen by others, and yourself, in case you delete your local folder or want to continue working on another computer. The exact command depends on your initial configuration, but don’t worry, lots of practical decisions are almost automatic.

# git remote add origin git@github.com:allixender/test.git

git push origin

# git push origin main

# git push origin master

# ... you will see, typically it's done once and you can just do "git push origin"

c) Existing online GitHub repository

If you have an own existing GitHub repository online, you would typically “clone” it into a local working directory.

git clone <your online GitHub repository URL>

Once you start relating between your local Git folder, your GitHub repository (in your account) and other online GitHub repositories, you need a few more things.

If you have changes in your upstream (origin, e.g. GitHub) that you know of and you need to update your local Git folder:

git pull origin

# git pull origin main

# git pull origin master

# ... you will see, typically it's done once and you can just do "git pull origin"

If you want to contribute to someone else’s GitHub repository, don’t immediately clone their repo into your local folder. Rather, create a fork online in GitHub, this will add a linked copy into your account. Then “clone” that repository from your account into your local working folder. Once you have “pushed” your local changes back online to your online GitHub repository, you can create a pull request to the other person’s original repository.

If you by any chance run into the situation that you have online and local accidentally changed the same file, you will run into a “merge conflict”, then “pull” will not be allowed by Git. Instead you will have “fetch” the changes and then merge (just really local manual deciding and updating) and “commit” and “push” the merged files again.

# assuming your default working branch is main (online aka origin)

# git fetch loads the online version without applying the changes

git fetch origin main

# with git merge you tell Git to apply changes from the origin/main branch to your local (main) working branch

git merge origin/main

# this can cause the message "merge conflict" and then tell you which files you'll have to "repair" or decide which is the more important one

# ... you editing the files

git add <the repaired target files>

git commit -m "fixed merge conflict"

git push origin main

Git Cheat Sheet for your convenience

ZENODO

Know how to deposit code and data in a indexed scientific repository with a DOI

Zenodo assigns all publicly available uploads a Digital Object Identifier (DOI) to make the upload easily and uniquely citeable. Zenodo further supports harvesting of all content via an open metadata sharing protocol.

(All) Research Shared, your one stop research shop!

Discoverable, be found!

create your own repository

more than just a drop box! Your research output is stored safely for the future in same cloud infrastructure as research data from CERN’s Large Hadron Collider and using CERN’s battle-tested repository software Invenio, which is used by some of the world’s largest repositories such as INSPIRE HEP and CERN Document Server.

Reporting - tell your funding agency! Zenodo is integrated into reporting lines for research funded by the European Commission via OpenAIRE.

Reproducibility guidelines

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reproducibility#Reproducible_research

Reproducible research is a crucial topic for any research domain using computational processes, including GIScience and EarthSciences. Recent research has shown, that many publications leave room for improvement regarding their computational reproducibility. The AGILE council generously supports an initiative for development of new guidelines for AGILE conference submissions to improve reproducibility. The planned duration of the initiative is January 2019 to June 2019. The initiative will prepare new author guidelines and reviewer guidelines suitable for all submission types (full, short, poster).

More skills - The Carpentries

Since 1998, Software Carpentry has been teaching researchers the computing skills they need to get more done in less time and with less pain. Our volunteer instructors have run hundreds of events for more than 34,000 researchers since 2012. All of our lesson materials are freely reusable under the Creative Commons - Attribution license.

The Software Carpentry Foundation and its sibling lesson project, Data Carpentry, have merged to become The Carpentries, a fiscally sponsored project of Community Initiatives, a 501(c)3 non-profit incorporated in the United States. See the staff page for The Carpentries.